The Initiative Triad

Difficulties with initiating voluntary action have a substantial impact on quality of life for people with various psychiatric and neurological conditions, yet they are largely neglected by formal research. Understanding of inertia is impeded by:

- the arbitrary distinctions between neurological, psychiatric, and neurodevelopmental conditions,

- the biases arising from the most obvious or ‘primary’ symptoms, and

- the enormous diversity of terminology (see 27 words for ‘stuck’).

In an ancient Indian parable, when six blind men encounter an elephant, each describes a very different impression based on what they can feel. This analogy can be useful for understanding the way volition is viewed across different neurological and psychiatric conditions. Just as the blind men describe the elephant as like a snake, tree or fan depending on whether they are touching the trunk, a leg or an ear, so our present day health care providers, educators and researchers describe impairments in voluntary action in terms or their expertise and the primary features of a condition.

In this way, a neurologist sees initiation impairments in Parkinson’s Disease and attributes them to a neurological deficit and calls them apathy; a psychiatrist sees lack of goal directed activity in schizophrenia and calls it avolition; and a behaviour therapist sees a lack of initiative in autism, considers it behavioural, and doesn’t acknowledge it as a separate issue at all. The separate theoretical approaches and terminology used to describe these difficulties gets in the way of investigation into the common underlying cognitive and biological mechanisms, just as the blind men are unable to conceive of the whole elephant.

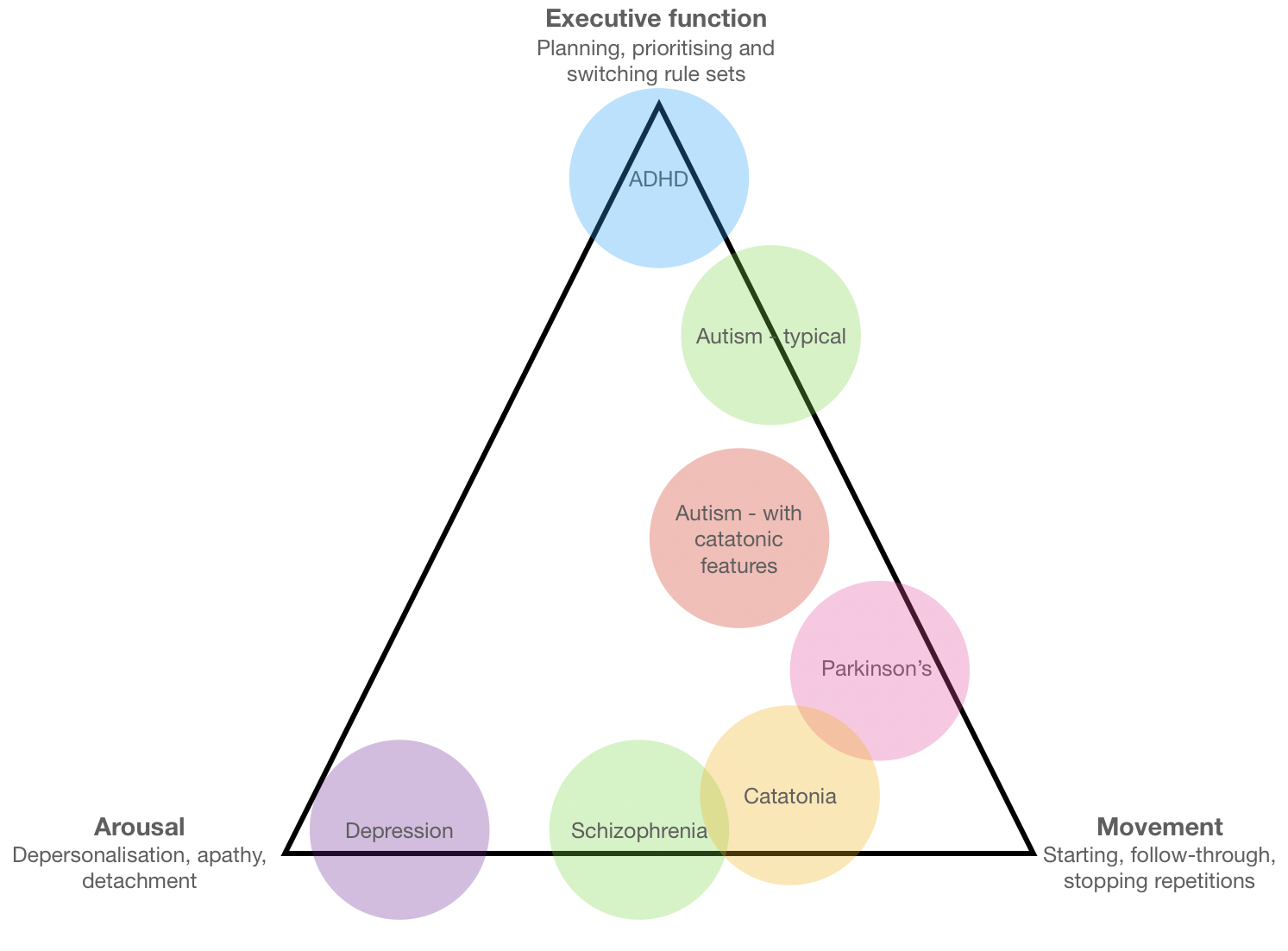

I started looking at this as a problem many autistic people have, but the most familiar description I ever read was by someone with Schizotypal Personality Disorder writing about avolition. Unfortunately, that blog no longer seems to exist, but it was one of the things that got me thinking about the overlap between avolition and autistic inertia. So I want to do some more research into that. The diagram below shows where I’m up to with my thinking. It’s a sketch to illustrate what I’m talking about and it is not meant to be taken as any kind of absolute. I have proposed to write an article about it; I will if I get both endorsement that it’s a good idea to do and the time to do it.

So this diagram shows three traits that often go together: difficulty with motor initiation (or follow-through), low emotional arousal or detachment, and difficulty with executive function. The conditions in the circles are some of the ones that share all three of these traits to varying degrees. Of course they also vary between individuals with the conditions, a person can have more than one condition, etc.. It is a work in progress, so while comments are welcome, try to go easy on me!

This is definitely an important idea to explore. I have a family member who has struggled with leaving the house and really stopped functioning for several years. Both autism and psychosis have been explored, and depression was the diagnosis at one stage. I work in mental health and know that behavioural interventions can be very effective with depression, but less so with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. I wonder where sense of self fits in – as there are often differences in self perception in autism and a loss of sense of self and disruptions in agency in psychosis. I look forward to reading your work on this is the future.

This is brilliant. As a therapist (and autistic person), I could easily use this diagram every day, if not multiple times a day.